From Words to Vectors: How Semantics Traveled from Linguistics to Large Language Models

Originally published on Dev.to on January 17, 2026.

Read the Dev.to version

Why meaning moved from definitions to structure — and what that changed for modern AI

When engineers talk about semantic search, embeddings, or LLMs that "understand" language, it often sounds like something fundamentally new. Yet the problems modern AI systems face — meaning, reference, ambiguity, and context — were already central questions in linguistics and philosophy more than a century ago.

This article traces how the concept of semantics evolved across disciplines: from linguistics and philosophy, through symbolic AI and statistical NLP, and finally into the neural architectures that power modern large language models, and why this history matters for how we design retrieval, memory, and language systems today. The journey reveals that today's AI systems are not a break from the past, but the convergence of long-standing ideas finally made computationally feasible.

Linguistic Origins: Meaning as a System, Not a Label

Modern semantics begins not with computers, but with language itself. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, linguists began to reject the naive idea that words simply "point" to things in the world. One of the most influential figures in this shift was Ferdinand de Saussure, who argued that language is a structured system of signs rather than a naming scheme.

Saussure proposed that each linguistic sign consists of two inseparable parts: the signifier (the sound or written form) and the signified (the concept evoked). Crucially, the relationship between the two is arbitrary. There is nothing inherently "dog-like" about the word dog. Its meaning arises because it occupies a position within a broader system of contrasts: dog is meaningful because it is not cat, not wolf, not table.

This was a radical idea at the time. Meaning, Saussure claimed, is relational. Words derive significance from how they differ from other words, not from direct correspondence with reality. This insight quietly laid the conceptual groundwork for everything from structural linguistics to modern vector-based representations.

Philosophy of Language: Meaning, Logic, and Composition

While linguists focused on structure, philosophers sought precision. In particular, Gottlob Frege transformed semantics by embedding it into formal logic. Frege introduced a critical distinction between sense — the mode of presentation of an idea, and reference — the actual object being referred to.

This distinction explained how two expressions could refer to the same thing while conveying different information. "The morning star" and "the evening star" both refer to Venus, yet they are not interchangeable in all contexts. Meaning, therefore, could not be reduced to reference alone.

More importantly, Frege formalized the idea of compositionality: the meaning of a sentence is determined by the meanings of its parts and the rules used to combine them. This principle became foundational not only in philosophy, but later in programming languages, logic systems, and early AI models.

In retrospect, compositionality is what allowed meaning to be treated as something computable, at least in theory.

Early Artificial Intelligence: When Meaning Was Symbolic

When I studied linguistics at university many years ago, everything up to this point was already part of the curriculum. Structural linguistics, philosophy of language, and formal semantics provided a solid theoretical foundation. What none of us could have anticipated at the time was how directly these ideas would later intersect with computer science in what would come to be called artificial intelligence.

When AI emerged as a field in the mid-20th century, it inherited philosophy's confidence in symbols and logic. Early systems assumed that meaning could be explicitly represented through formal structures: symbols, predicates, rules, and ontologies. To "understand" language was to transform symbols according to carefully designed rules.

For a while, this worked. Expert systems, knowledge graphs, and first-order logic engines achieved impressive results in narrowly defined domains such as medical diagnosis, chemical analysis, and configuration problems. Within carefully bounded worlds, symbolic semantics appeared tractable.

Natural language, however, quickly exposed the limits of this approach. Human language is ambiguous, context-dependent, and constantly evolving. Encoding all possible meanings and interpretations proved not merely difficult, but fundamentally unscalable. Symbolic systems were brittle: they failed not gradually, but catastrophically, when faced with inputs that deviated even slightly from their assumptions.

Semantics, it turned out, was far messier than logic had allowed, and far more resistant to being fully written down.

The Statistical Shift: Meaning Emerges from Usage

A quiet revolution began when linguists and computer scientists started to look not at rules, but at usage patterns. The idea that meaning could be inferred from how words are used rather than how they are defined gained traction in the mid-20th century.

The core insight was simple but profound: words that appear in similar contexts tend to have similar meanings. Instead of encoding semantics explicitly, one could measure it statistically by analyzing large corpora of text.

This approach, known as distributional semantics, reframed meaning as something empirical rather than prescriptive. Words became vectors of co-occurrence statistics. Similarity was no longer binary or rule-based, but graded and approximate.

This was a decisive break from symbolic AI and a return, in spirit, to Saussure's relational view of meaning.

Word Embeddings: Geometry Becomes Semantics

Distributional ideas matured dramatically with the introduction of neural word embeddings, particularly models like Word2Vec. Instead of relying on sparse frequency counts, these models learned dense, low-dimensional vector representations optimized to predict linguistic context.

What emerged surprised even their creators. Semantic relationships appeared as geometric regularities in vector space. Differences between vectors encoded analogies, hierarchies, and semantic proximity. Meaning became something you could measure with cosine similarity.

This was not symbolic understanding, but it was not random either. It was structure: learned rather than designed.

For the first time, machines exhibited behavior that looked like semantic intuition, despite having no explicit definitions or rules.

Contextual Semantics: Meaning Is Not Fixed

Static embeddings had a fundamental limitation: each word had exactly one vector, regardless of context. But human language does not work that way. The meaning of a word shifts depending on surrounding words, speaker intent, situation, and even emotion.

Transformer-based models, particularly BERT, addressed this by making representations contextual. Instead of asking "What does this word mean?", the model learned to ask "What does this word mean here?"

Through attention mechanisms, transformers model relationships between tokens dynamically. Meaning is no longer stored in a single vector per word, but distributed across layers and activations that respond to context.

This marked a crucial step toward pragmatic semantics: language as it is actually used, not as it is abstractly defined.

Large Language Models: Semantics as Emergent Structure

Large language models such as GPT do not contain explicit semantic representations in the traditional sense. They are trained to predict the next token in a sequence. And yet, at scale, they display behaviors that look strikingly semantic: summarization, reasoning, translation, abstraction.

The key idea is emergence. As models compress vast amounts of linguistic data, they internalize regularities about the world, language, and human communication. Semantics arises not as a module, but as a side effect of learning efficient representations.

These models do not "know" meaning in a philosophical sense. But they operate in a space where syntax, semantics, and pragmatics are inseparable, and where relational structure dominates.

When Meaning Becomes Operational

For practitioners building semantic search systems, RAG pipelines, or LLM-adjacent infrastructure, this history is not academic background — it is an explanation of why certain designs consistently work while others fail. Exact matching breaks down because natural language rarely repeats itself verbatim. Embeddings succeed not because they are clever, but because they mirror how meaning behaves in practice: approximately, relationally, and with tolerance for variation.

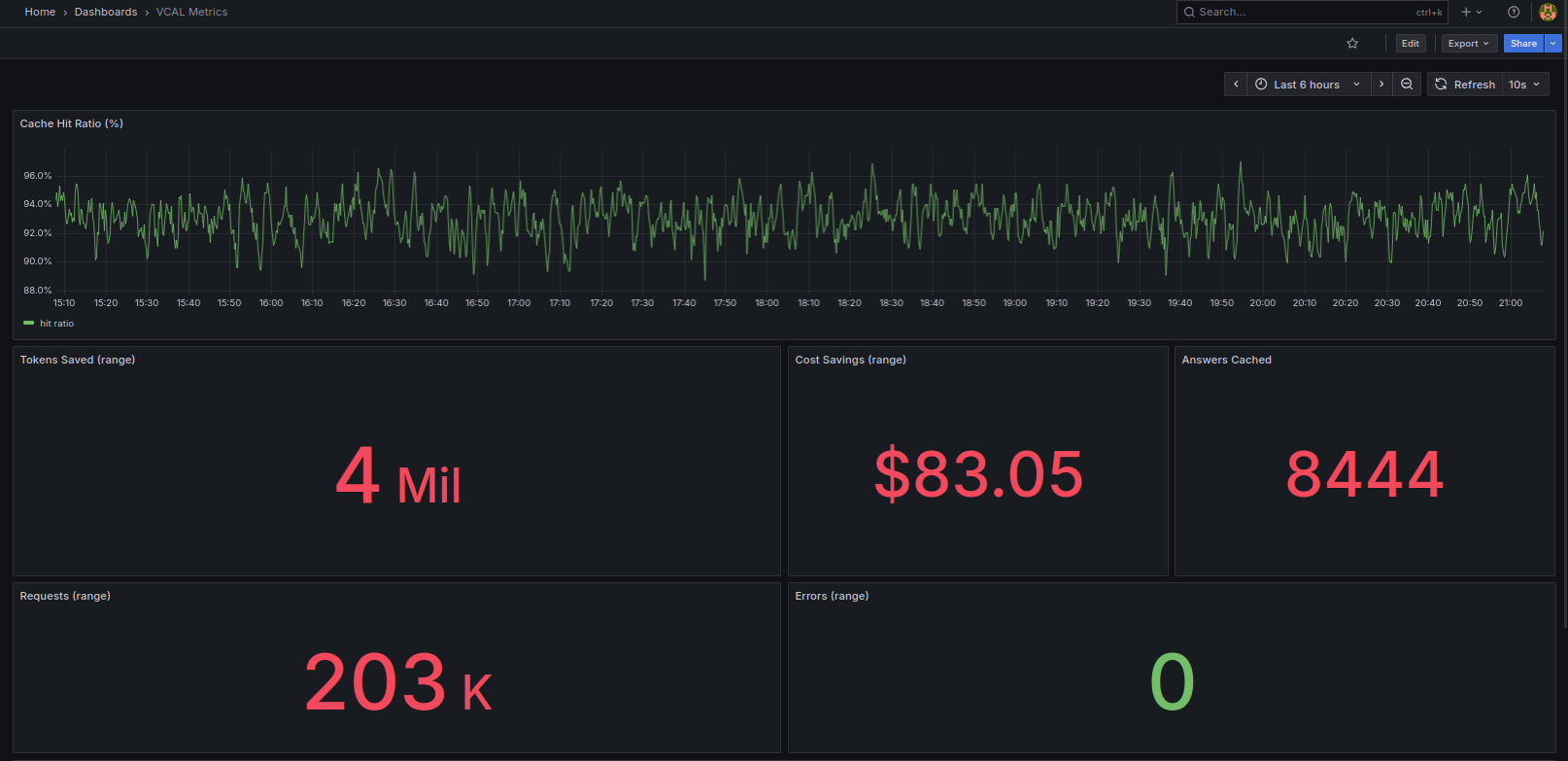

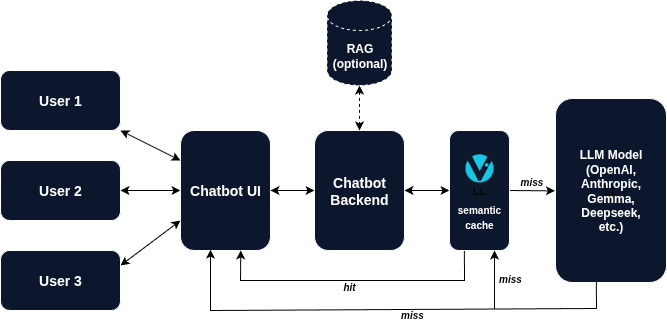

Once this is understood, several architectural consequences follow naturally. Retrieval quality depends less on perfect recall and more on selecting representations that preserve semantic neighborhoods. Caching strategies become viable only when equivalence is defined by similarity rather than identity. Evaluation metrics must account for graded relevance instead of binary correctness. Even system boundaries shift: components no longer exchange "facts", but approximations of meaning that remain useful within context.

Semantic systems are effective precisely because they do not attempt to eliminate ambiguity. They absorb it. Whether you are designing a vector store, placing a semantic cache in front of an LLM, or building a long-term memory layer for conversational systems, you are implicitly making choices about how much approximation your system tolerates and where that tolerance is enforced.

Closing Thought: Semantics as Shared Infrastructure

What began as a linguistic insight, that words gain meaning through their relations to other words, has quietly become an organizing principle for entire computational systems. Meaning no longer lives in dictionaries, rules, or symbols, but in patterns: in how expressions cluster, diverge, and reappear across vast landscapes of language. Semantics is no longer something a system contains; it is something a system moves through.

This shift took more than a century to unfold. It required philosophers to separate sense from reference, linguists to abandon naming theories, and engineers to accept approximation over certainty. Only when data became abundant and computation relatively cheap did this long trajectory converge into something operational. Semantics, once debated in lecture halls and footnotes, has become infrastructure — implicit, distributed, and shared.

That idea, radical when first proposed, has been waiting over a hundred years for enough data and compute to become practical.

And now, finally, it has.